A Common Thread in 2019 CFPB Enforcement Activity: Denials of Petitions to Set Aside CIDs

As promised, we return now to provide an overview of the CFPB’s petition activity for the year to-date. In addition to the Bank of America (BofA) petition denial we discussed last month, the CFPB has issued a series of decisions denying petitions to modify or set aside civil investigative demands (CIDs).

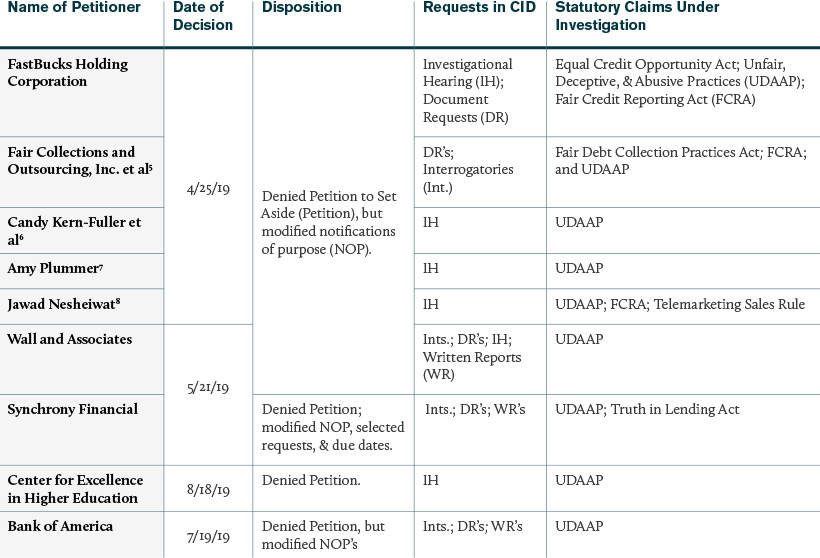

Within the first ten months of Director Kathleen Kraninger’s tenure at the CFPB, the agency has published decisions on nine petitions to modify or set aside CIDs. The eleven entities and individuals challenging the CID through its administrative process argued primarily that the CID in question had been issued for an improper purpose or that compliance would be unduly burdensome. Each and every such argument in the petition was denied on the merits.

The CFPB Director, however, did grant some petitions in part, insofar as the Director modified the CID to clarify the Notification of Purpose box. While these concessions may better inform the subject of investigation as to the reason for a sweeping probe, from a practical standpoint such clarification would not reduce tangible compliance costs, as requested.

Importantly, the approach of the CFPB Director to support agency enforcement can be illustrated in the following four examples of petition denials:

-

On April 25, 2019, the Director denied Fastbucks Holding Corporation’s request to set aside or modify three CIDs seeking information as to whether Fastbucks and its lenders had violated the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, the Fair Credit Reporting Act, or had engaged in unfair, deceptive or abusive acts or practices in violation of the Consumer Financial Protection Act.[1] There, Fastbucks alleged that “harass[ing] and taunt[ing]” messages, which were allegedly sent via social media by an individual at the CFPB to the company’s CEO, showed the CID had been issued for an improper purpose. Fastbucks argued in its petition that prior Acting Director Mick Mulvaney had vowed that the CFPB would conduct itself with “humility and prudence,” and the investigation of Fastbucks had hallmarks that contradicted such a humble or prudent approach. Director Kraninger denied the petition, standing by the Enforcement staff, and asserting that the agency as an entity did not improperly issue the CID notwithstanding the petitioner’s concern regarding the behavior of one CFPB employee.

-

The same day, CFPB issued an Order concerning the petition filed by Fair Collections and Outsourcing, Inc., et al., which asserted among other things that the CID was invalid because the CFPB was unconstitutional. The Director rejected that argument, as well, and enforced the CID.

-

On May 21, 2019, the Director similarly denied a petition to set aside or modify a CID that had been issued to Synchrony Financial (formerly, GE Capital). Such CID stated that the purpose of the CFPB’s investigation was to determine whether banks (or card issuers) had committed misleading advertising, wrongful payment-allocation, or other untoward practices in connection with deferred-interest financings on consumer credit cards.[2] Despite finding that Synchrony “failed to demonstrate the sort of burden that would justify setting aside or modifying the CID,” the CFPB modified the CID in a narrow fashion unlike the consequences of what would occur in a negotiated meet-and-confer process, i.e., the CFPB limited the scope of certain requested items and extended deadlines.[3]

-

On September 6, 2019, the Director likewise denied a petition to set aside or modify a CID against the Center for Excellence in Higher Education (CEHE).[4] CEHE argued that complying with the CID was unduly burdensome, and that seeking testimony as to “every aspect” of the company’s student loan program was unreasonable. The Director rejected this argument and issued an order compelling compliance with the CID. Notably, the Director decided in favor of the CFPB and against CEHE, a nonprofit organization that was alleged to have offered student loans, notwithstanding some outcry among advocates that the CFPB’s recent appointment of a Private Education Loan Ombudsman (who formerly served as a top official at a loan servicer) was a harbinger that the CFPB would no longer protect the interests of student borrowers. Director Kraninger’s petition denial suggests the contrary.

Below we provide a graph detailing the outcome of the remaining cases not discussed above in our case summaries, or in our prior blog post about Bank of America.

Director Kraninger’s Petition Decisions in 2019

Four Strategic Takeaways from Petition Denials

First, the decisions, including the CEHE and Fastbucks decisions,[9] indicate that the CFPB and state attorneys general are furthering their shared objective to coordinate investigations. Accordingly, Director Kraninger’s tenure thus far demonstrates that the CFPB has not changed its protocol of pursuing deliberate state-federal joint investigations of consumer financial protection violations. While popular press have been reporting that federal enforcement agencies under the current administration have been defanged, leaving a void into which state agencies have stepped up, the plain facts (and the docket of petition denials at the CFPB) indicate that—in actuality—federal-state coordination of investigations remains robust, consistent with the CFPB’s mission.

Second, the petition denials represent continued adherence to judicial precedent arising out of similar challenges to investigative demands issued by other agencies, most notably the Federal Trade Commission. While Director Kraninger’s tenure began less than a year ago, the Director’s decisions rested on United States Supreme Court precedent more than sixty-nine years old, which have established that “courts should not refuse to enforce an administrative subpoena when confronted by a fact-based claim regarding coverage.”[10] Meaning, arguments regarding the application of the law or determining a violation are premature in the investigation phase.

Similarly, Director Kraninger relied upon the legal principles long-held by federal appellate courts nationwide in deciding challenges to agency administrative subpoenas, including the twenty-six years of judicial precedent established by the DC Circuit, which explains: “the standard for judging relevancy in an investigatory proceeding is more relaxed than an adjudicatory one.”[11] These developments reveal that, under this administration, recipients of CIDs who harbor grievances concerning a CIDs contents are now on notice that their arguments must be presented in a way that is consistent with these case precedents, or else face likely denial of the petition.

Third, we wrote in our article published in The Review of Banking & Financial Services about how the CFPB persists in requiring oral testimony, under oath, at investigational hearings. The petition denials of 2019 further bolster our thesis that the CFPB’s requests for sworn testimony in enforcement matters are ubiquitous in investigations.

Fourth, the aspects of Orders “granting in part” the CID challenges (see footnote 1 and above chart) represent a response to other external and internal pressures in the lead-up to these decisions. As to external pressure, in litigated matters, the CFPB had been rebuked by the Fifth Circuit last September, when the federal appellate court ruled that the CID in question failed to identify the purported violation under investigation or how the subject activities violated the law, and ruled that the CID was not to be enforced as a result.[12] As to internal pressures, the CFPB is currently grappling with the actions of former CFPB Acting Director Mick Mulvaney (now the current Acting White House Chief of Staff, presently embroiled in non-CFPB-related controversies) involving commencement of a public Request for Information (RFI) process, eliciting 157 comment letters, to gather information concerning the efficacy of the CFPB’s processes for Civil Investigative Demands. [13] Rather than issuing a new regulation reforming the CID process in response to the 157 comment letters, many of which were critical of the CFPB, the current CFPB leadership instead appears so far to prefer to ensure required specificity in the Notification of Purpose box—whether in the initial draft CID or in response to a challenged CID in the petition process.

Rather than weakening the CFPB, the RFI-process led by former Acting Director Mulvaney has had one arguable effect of strengthening the CFPB’s ability to write better CIDs that are more defensible in court.

Looking Forward

So long as the CFPB desires to follow judicial precedent, the 2019 Orders show that the burden to modify a CIDs terms through the formal petition process will likely remain high. With the relatively inactive CFPB press office, however, the public reputational harm from lodging a petition may be lower than under the Obama Administration. While this causes CID recipients to arguably become more willing to avail themselves of the petition process, the actual outcome of such process remains pretty similar to what industry participants felt under former Director Richard Cordray: denials of substantive arguments to set aside the investigatory probes. Moreover, Enforcement staff remain amenable to making recommendations for CID modification, such as rolling productions or working with companies or institutions to reduce the burden of CID requests, if companies meet the standard for modifications.

Moving forward, given the greater interest of the CFPB to reform its processes internally than to take positions publicly that are critical of its own operations, in some circumstances, CID recipients may get better traction from negotiations with Enforcement staff than from a petition process.

[1] Decision and Order on Petition by Fastbucks Holding Corp. to Modify or Set Aside Civil Investigative Demands (April 25, 2019).

[2] CFPB’s Decision and Order on Petition by Synchrony Financial to Set Aside or Modify the August 28, 2018, Civil Investigative Demand (May 21, 2019).

[3] Id. at 9.

[4] CFPB’s Decision and Order on Petition by Center for Excellence in Higher Education to Set Aside or Modify the April 12, 2019, Civil Investigative Demand (August 18, 2019), (CEHE Decision).

[5] Decision and Order on Petition by Fair Collections and Outsourcing, Inc. and Fair Collections and Outsourcing of New England, Inc. to Modify or Set Aside Civil Investigative Demand (April 25, 2019).

[6] Decision and Order on Petition by Candy Kern-Fuller and Howard E. Sutter III to Modify or Set Aside Civil Investigative Demand (April 25, 2019).

[7] Decision and Order on Petition by Amy Plummer to Modify or Set Aside Civil Investigative Demand (April 25, 2019).

[8] Decision and Order on Petition by Jawad Nesheiwat to Modify or Set Aside Civil Investigative Demand (April 25, 2019).

[9] In those matters, the publication of the CFPB’s decision on the petition demonstrated that the agency is coordinating with Colorado and New Mexico.

[10] EEOC v. Karuk Tribe Housing Auth., 260 F.3d 1071, 1076 (9th Cir. 2001) (citing Okla. Press Publ’g Co. v. Walling, 327 U.S. 186, 216 (1946)); United States v. Morton Salt Co., 338 U.S. 632, 652-53 (1950).

[11] Resolution Trust Corp. v. Walde, 18 F.3d 943, 947 (D.C. Cir. 1994) (quoting FTC v. Invention Submission, 965 F.2d 1086, 1090 (D.C. Cir. 1992).

[12] Consumer Fin. Prot. CFPB v. The Source for Public Data, L.P., 903 F.3d 456, 458 (5th Cir. 2018). This ruling was not unlike the D.C. Circuit’s decision in the ACICS matter, where the court held that the CFPB’s reliance upon broad and nondescriptive terminology on the face of the CID failed to constitute reasonable notice of a purported violation. Consumer Fin. Prot. CFPB v. Accrediting Council for Indep. Colleges & Schs. (ACICS), 854 F.3d 683, 690-91 (D.C. Cir. 2017).

[13] Acting Director Mulvaney Announces Call for Evidence Regarding Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Functions, Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau (Jan. 17, 2019).

Arent Fox’s Consumer Financial Services group will continue to monitor developments in this area. If you have any questions, please contact Jenny Lee, Susan Tran, Elyssa Evans, or the Arent Fox professional who usually handles your matters.

- Related Practices